|

| Richard H. Anderson (courtesy of National Park Service) |

The disintegration of R. H.

Anderson’s division can be seen distinctly from the official reports of its

brigades: there are none. Not only did no official report for the division find

its way into the published Official Records; there is also none for any

of its six brigades, and only a report for one of the twenty-six regiments that

made up those brigades. The report of Capt. Abram M. “Dode” Feltus, senior

officer present with the 16th Mississippi, is the only one in that standard

source out of a potential thirty-three documents. The lacuna frustrates

historians; it also illustrates the paucity of command in the division on

September 17 (and the haphazard way in which R. H. Anderson administered his

division when he returned to its command).[1]

Volume Three of the Supplement to the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, published in 1994, contains a brief (and useless when it comes to Antietam) paragraph written by Col. William A. Parham, commanding Mahone’s brigade, and a report for Ambrose Wright’s brigade written by Col. William Gibson, third in charge of the brigade and its commander at the close of battle on September 17. These two sources bring the number of documents from Anderson’s division up to three out of the 33 Krick counted. Now, here is the fourth (Krick cites Herbert's report but since it was written in 1864 likely does not count it as an after-action report). It has been cited before in other works but has been used sparingly in studies of the Maryland Campaign.

In 1977, Maurice Fortin published Maj. Hilary Herbert’s History

of the Eighth Alabama Volunteer Regiment, C.S.A. in the 1977 issue of The

Alabama Historical Quarterly. Herbert was the commanding officer of the 8th

Alabama, part of Wilcox’s brigade, at the Battle of Antietam. I stumbled upon Fortin’s

work while researching Herbert’s interesting postwar career.

|

| A postwar image of Hilary Herbert (Harvard Art Museum) |

Leaving Sharpsburg to our right we made a detour to our

left, passing beyond the town and through open fields exposed for a half mile

to a withering fire of artillery. Rising a hill into an apple orchard[2]and

still marching by the right flank, we came within grape shot range of the enemy’s

batteries and within reach of their small arms. We moved forward through a

field of corn,[3]which

sloped downward from an orchard (near Pfeiffer’s house), and went ‘forward in

line,’ on the right opposite the enemy. (Before we had gotten into line Colonel

Cumming,[4]

commanding the brigade, was wounded and compelled to leave the field.) The

fight now became furious. Our Division occupied about the right center of the

line, our Brigade on the right of the Division. On the right of the Brigade was

a gap in the line unoccupied. (So great was this gap that no Confederates were

in sight on our right.) Before getting into position we had lost heavily;

Captain Nall[5]had

been temporarily disabled by a shell and Lieutenant (A. H.) Ravesies,[6]acting

Adjutant, had received a severe wound in the leg.

A compact line of infantry about 120 yards in our front

poured a well-directed fire upon us, which we answered rapidly and with effect.

A battery of artillery about forty-five degrees to our

right[7](A

conversation with Federal General [Ezra A.] Carman whom on a recent visit I found

in charge of the battlefield now under Government supervision, developed the

fact that this battery was on a height across the Antietam river.) and another

at a similar angle on our left,[8]concentrated

shells upon us with terrible accuracy. We were unsupported by any artillery on

our portion of the line.

Sergeant J. P. Harris, bearing the flag, was soon

wounded. Corporal Thomas Ryan of Company E immediately took the colors and was

shortly afterwards mortally wounded.

|

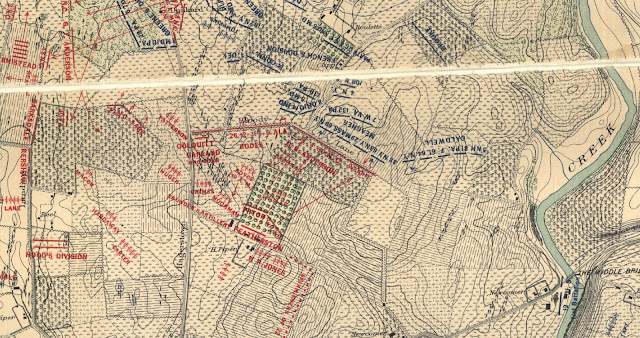

| The 10:30 a.m. Antietam Battlefield Board map shows the movement of Wilcox's Brigade, which included the 8th Alabama, through the Piper Orchard and Cornfield. |

Sergeant James Castello of Company G then seized the flag. Ammunition was being exhausted and men were using the cartridge boxes of their dead and wounded comrades. The enemy’s line in front of us wavered and portions of it broke, but it was re-inforced by fresh troops. Our line to the left was being pushed back by overwhelming numbers. Major Herbert gave the order to the regiment, and we fell back slowly. About three hundred yards in the rear we found Major (John W.) Fairfax, General Longstreet’s ‘Fighting Aide’ as the soldiers called him, endeavoring to rally the troops that had fallen back before us.

Despatching Lieutenant (M. G.) McWilliams (of Co. B.) and

two men after ammunition, Major Williams (of the 9th)[9]and

Major Herbert railed about 100 men of the brigade and moved forward again.

Rising the hill into the apple orchard before spoken of, the enemy were

observed coming through the cornfield in front in a strong line. Pouring a

volley into them and charging them with a shout, we routed them completely.

They rallied, however, and seeing how few we were, formed behind a rock fence

on the opposite ridge about 100 yards distant. Taking post in the orchard, the

unequal fire was kept up until our numbers gradually melting away under the

fire of the enemy (Note: The batteries over the river were firing on us.), it

became impracticable to hold the ground longer, and the order was given to

retire.

Major Williams had now been wounded and the command of

the Brigade devolved on Major Herbert, who rallied about fifty men and again

advanced to the apple orchard. Here the combat was renewed with exactly the

same result. The enemy were again advancing through the cornfield, were again driven

back, and again took position behind the rock fence. We retained our position

in the apple orchard and continued the fight, the enemy’s balls playing fearful

havoc in our ranks. The flag bearer, Sergeant Castello, whose gallantry had

been conspicuous throughout the day, received a musket ball through the head. Major

Herbert took up the colors, but shortly afterwards gave them to Sergeant G. T.

L. Robinson of Company B,[10]

who insisted upon his right to carry them. Soon he too fell wounded, and

Private W. G. McCloskie of Company G[11]took

the flag and carried it gallantly through the day. (Thus the flag that day was

carried successively by five different persons.)

From their position behind the rock fence, and with the

artillery across the Antietam, the enemy commanded the orchard. It, therefore,

became necessary to fall back again, which was done by order, the enemy not

again attempting to occupy the disputed ground until later in the evening.

It was near sunset; A. P. Hill’s Division had come up and

was hotly engaged with the enemy on our right. (The gap on our right heretofore

spoken of as unoccupied was the gap between us and A. P. Hill. We saw no one on

our right till A. P. Hill came up.) The enemy making no further attempt against

our portion of the line we had moved over to support General A. P. Hill’s left.

The enemy (those in our former front) now attempted to gain such a position as

to command our left flank.[12]

Brigadier General (Philip) Cook, commanding a brigade of

Georgians[13]

and with whom Major Herbert was now cooperating, saw this movement, and we

changed front to meet it. The nature of the ground permitted us to shift our

position without being seen. The enemy now came confidently forward. We were in

line just in front of them but concealed by the crest of a hill. When they

arrived within thirty yards of us we rose, poured a volley into, and charged

them. They fled in confusion, leaving us in possession of the oft-disputed

apple orchard and seventeen prisoners besides their wounded. (Note: This

possession was only temporary. The artillery over the river compelled us to

seek shelter back of the hill behind us.) Thus closed the battle along our

position of the line.

On the next day we held our position but there was no

serious engagement. (Note: We lost one man under very singular circumstances.

He was with the regiment which was lying in its position of the evening before,

when a musket ball killed him coming from the enemy’s direction, but we heard

no sound of a gun nor did we see or hear any skirmishing during the day.) Our

loss in this battle was seventy-eight killed and wounded out of 120 carried

into the fight. After the battle, the following men were complimented for

gallantry in special orders from regimental headquarters.

Sergeant

G. T. L. Robinson, now Captain, Company B.

Sergeant G. B. Gould. Company

G (later appointed 2nd Lt. for gallantry).[14]

Sergeant George Hatch, Company

F (later 1st Lt.).

Sergeant (Charles F.) Brown,

Company D (later 2nd Lt.).

Private L. P. Bulger, Company

B (afterwards Sergeant and killed at Gettysburg).

Private W. G. Mccloskie,

Company G.[15]

Private James Ryan, Company I.

Private Peter Smith, Company

G.

Private Charles Rob, Company

G.

Private John Herbert, Company

H.

Private John Callahan, Company

C.

“Here ends the official account of the battle written at

Orange, C. H.,” Herbert concluded. In his personal narrative about the Battle

of Antietam, Herbert also included “the roll of honor as made up by the men for

this battle”:

Corporal

David Tucker, Company A.

Private John Curry, Company C.

Sergeant T(homas) S. Ryan,

Company E.

Sergeant James Castello,

Company G—killed.

Private J(ohn) Herbert,

Company H—killed.

Private O. M. Harris, Company

K—killed.

Private G. T. L. Robinson,

Company B.

Private C. F. Brown, Company

D.

Corporal J. R. Searcy, Company

F.

Private James Ryan, Company I.

“It will be seen that this roll of men is somewhat different

from the list of those specially complimented in Major Herbert’s order from

regimental headquarters,” wrote Herbet, “the men desiring to honor some not

specially mentioned in the regimental order.”

In his history of the 8th Alabama, Herbert wrapped up his

chapter on Antietam with the following postscript related to his 1864 report of

the regiment’s actions on September 17, 1862:

[1] Krick, “It Appeared As

Though Mutual Extermination Would Put a Stop to the Awful Carnage: Confederates

in Sharpsburg’s Bloody Lane,” 240.

[2] Piper Orchard.

[3] Piper Cornfield.

[4] Col. Alfred Cumming.

[5] Capt. Ducalion "Duke" Nall (1827-1864), wounded at Sharpsburg, mortally wounded at the Battle of the Wilderness.

[6] 1st Lt. Augustine Henry Ravesies (1838 - 1906).

[7] Either Lt. Bernhard Wever’s

Battery A, 1st Battalion, New York Light Artillery, or Capt. Robert Langner’s

Battery C, 1st Battalion, New York Light Artillery.

[8] Either Capt. Charles Owen’s

Battery G, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, or Capt. John Tompkins’ Battery A,

1st Rhode Island Light Artillery.

[9] Maj. Jeremiah “Jere” Henry

Johnston Williams.

[10] 1st Sgt. George T. L. Robison (1843-1877).

[11] Possibly Pvt. Mathias J. McCosker, Co. G.

[12] 7th Maine Infantry.

[13] Lt. Col. Philip Cook, 4th

Georgia Infantry. Col. George Doles, 4th Georgia Infantry, rose to command

Ripley’s brigade when Brig. Gen. Roswell Ripley was wounded. No source,

excepting this 8th Alabama report, indicates that Doles relinquished command of

the brigade to Lt. Col. Cook.

[14] Sgt. Brainard Elisha Gould (1838-1891).

[15] See note 11.

[16] Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox.

[17] This corroborates Krick’s

statement above about R. H. Anderson’s administration of his division.

[18] Carman, Clemens

ed., The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, vol. 2, 602, tallies

the brigade’s casualties as 244 total.

[19] Herbert’s report and the

italicized sections of this article can be found in Maurice S. Fortin, ed.

“Colonel Hilary A. Herbert’s ‘History of the Eighth Alabama Volunteer Regiment,

C.S.A.,” The Alabama Historical Quarterly 39 (1977): 77-84.

The full digital edition of Fortin’s article can be found at https://archive.org/details/alabama-historical-quarterly-v39n0104.

11 comments:

Thanks! Kevin for bringing this account to the fore. Also thanks for annotating it. Very useful !

Thanks, Jim. I took that from your blog's playbook!

A valuable addition to the record that I had never seen before, KP. Thank you for posting it!

Thank you for this, Kevin. More names to look into!

You're welcome, thanks for reading it!

Brian, you were one of the first people I thought of when I began reading all of those names. I hope you find some information about them.

I have been curious about the rules regarding the writing of reports after a battle. Was it required in army regulations that an officer file a report? Was there anything punitive in nature that could be done to force an officer to submit a report?

Also, Kevin, you quote Krick as being critical of the way in which R.H. Anderson administered his division over the lack of reports. But shouldn't some of that criticism be directed at Longstreet? After all, he was Anderson's commanding officer and had to notice the almost complete lack of reports from the division.

I have been curious about the rules regarding the writing of reports after a battle. Was it required in army regulations that an officer file a report? Was there anything punitive in nature that could be done to force an officer to submit a report?

Also, Kevin, you quote Krick as being critical of the way in which R.H. Anderson administered his division over the lack of reports. But shouldn't some of that criticism be directed at Longstreet? After all, he was Anderson's commanding officer and had to notice the almost complete lack of reports from the division.

I have been curious about the rules regarding the writing of reports after a battle. Was it required in army regulations that an officer file a report? Was there anything punitive in nature that could be done to force an officer to submit a report?

Also, Kevin, you quote Krick as being critical of the way in which R.H. Anderson administered his division over the lack of reports. But shouldn't some of that criticism be directed at Longstreet? After all, he was Anderson's commanding officer and had to notice the almost complete lack of reports from the division.

Thanks in advance for any comments.

Yes, regulations did require commanders to submit reports to their superior officers. I'm not sure what measures could have been taken against an officer, though, who did not file a report.

With this in mind, criticism of either commander may be unfair, as it is likely reports were written from Anderson's division but they no longer survive, possibly consumed in the flames of Richmond in April 1865. But yes, superior officers and their staffs were responsible for enforcing the writing of after-action reports.

Post a Comment