I had always thought of the fight for the Burnside Bridge as one of infantry. The 2nd and 20th Georgia stoutly defending the bridge and the charge of the 51st New York and 51st Pennsylvania dominate our interpretation of the action there. It was not until today while hiking the Burnside Bridge sector of the Antietam battlefield with my good friend and artillery guru Jim Rosebrock (check out his excellent blog here) that I realized how crucial of a role Ambrose Burnside's and Jacob Cox's artillery played in cracking the conundrum of how to get their men across Antietam Creek.

The 9th Corps had 53 guns at Antietam, according to Curt Johnson's and Richard C. Anderson, Jr.'s book Artillery Hell. At various points of the fight for the Burnside Bridge, anywhere from 21 to 29 of those guns fired directly on the Confederate infantry defending the bridge or the nearby Confederate artillery that supported the infantry.

As attack after attack against the bridge and its Confederate defenders failed, there is a marked effort on the part of Burnside, Cox, and 9th Corps artillery chief George Getty to use artillery to drive the enemy away from the banks of Antietam Creek. While the 9th Corps' position always allowed it to converge the fire of its artillery onto the Confederate defenders, as the day wore on, 9th Corps batteries began shrinking their ring of fire, ensnaring the Confederates and ultimately helping drive them away.

Saturday, February 2, 2019

Tuesday, January 22, 2019

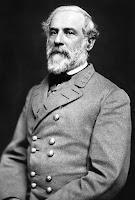

A Game of Numbers: Robert E. Lee's Assumptions about the Federal Garrisons in the Shenandoah Valley

Standing and fighting at Sharpsburg. Pickett's Charge. Each of these decisions could rightfully be labeled as Robert E. Lee's greatest mistake during his Civil War career. But one that often flies under the radar is the decision Lee made earlier in the Maryland Campaign to divide his army and send a large portion of it into the Shenandoah Valley to subdue the Federal garrisons positioned in Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry. A bold plan to be sure, this plan alone was not the undoing of Lee's campaign. Instead, it was the assumptions he made about how quickly his soldiers could open the Confederate supply line in the Shenandoah Valley.

Robert E. Lee was aware of the Union garrisons in the Valley before his men set foot on Maryland soil. But his crossings near Leesburg armed him with the belief that his intervention between those garrisons and Washington City and Baltimore would force the evacuations of Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry. It did not. Before Lee could advance his army farther north into Pennsylvania, he had to deal with the enemy in his rear to open the Valley as a supply route and, if needed, route of retreat back to Virginia.

On the evening of September 9, 1862, staff officers and couriers emanated from Lee's headquarters outside of Frederick. The riders delivered multiple copies of Special Orders No. 191 to Lee's subordinates. The orders outlined the division of the Army of Northern Virginia into multiple pieces, three of which, led by Stonewall Jackson, Lafayette McLaws, and John Walker, would take different routes to intercept, destroy, or capture the enemy garrisons at Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry. When the orders went into effect the next day, Lee anticipated that these three wings would wrap up the operations in the Valley quickly--perhaps as early as September 12--before the army reunited and continued on its trek north.

|

| Robert E. Lee |

On the evening of September 9, 1862, staff officers and couriers emanated from Lee's headquarters outside of Frederick. The riders delivered multiple copies of Special Orders No. 191 to Lee's subordinates. The orders outlined the division of the Army of Northern Virginia into multiple pieces, three of which, led by Stonewall Jackson, Lafayette McLaws, and John Walker, would take different routes to intercept, destroy, or capture the enemy garrisons at Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry. When the orders went into effect the next day, Lee anticipated that these three wings would wrap up the operations in the Valley quickly--perhaps as early as September 12--before the army reunited and continued on its trek north.

Sunday, January 13, 2019

John Pope's Take on Joseph Mansfield

John Pope's personality is often viewed negatively by historians. Quotes from Pope haters can be easily found and are often repeated in Civil War historiography. Sometimes, it reaches the point where one wonders if anyone could have gotten along with him or vice versa.

Pope's Military Memoirs, edited by Peter Cozzens and Robert I. Girardi, offer an eye-opening look into this divisive general. One quote in particular though caught my attention. It was Pope's description of Joseph Mansfield and his personality, looks, and bravery. Quotes like this are revealing, especially when Pope ties Mansfield's personality traits to his fate at Antietam. The two served together in Mexico, Mansfield as Pope's superior officer. "Pope took to Mansfield at once," wrote Pope's biographer Peter Cozzens. It appears Pope's favorable view of Mansfield remained until his dying day.

General Mansfield was of middle height and robust figure. He had a broad and rather ruddy face, with a thick shock of white hair and beard. He was a man of kindly disposition and very just; but, as I have said before, he was rather fussy and fond of meddling with his subordinates, so that, although all of his officers exulted in his behavior in battle and were immensely proud of him for some time after the battle was over, he soon reduced them to their old feeling that he tormented and persecuted them unwarrantably. He was still a comparatively young man when he was killed at Antietam, but I think it may be said of him that his complete recklessness and his apparently irresistible inclination to seek the most exposed and most dangerous places on a field of battle, of necessity deprived him of the power to use his great military abilities and acquirements to the best advantage for the army or the government. He was a gallant soldier and a true and loyal man and will always be remembered with pride and respect by those who knew him in those old days.

Pope's Military Memoirs, edited by Peter Cozzens and Robert I. Girardi, offer an eye-opening look into this divisive general. One quote in particular though caught my attention. It was Pope's description of Joseph Mansfield and his personality, looks, and bravery. Quotes like this are revealing, especially when Pope ties Mansfield's personality traits to his fate at Antietam. The two served together in Mexico, Mansfield as Pope's superior officer. "Pope took to Mansfield at once," wrote Pope's biographer Peter Cozzens. It appears Pope's favorable view of Mansfield remained until his dying day.

|

| Joseph K. F. Mansfield |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)