|

| Sgt. Russell Crawford Mitchell (left) and his granddaughter Margaret Mitchell (right) |

Sunday, October 27, 2019

Ancestors of Two Twentieth-Century Hollywood Influences Clash in Antietam's Cornfield

Some of the most popular movies portraying the Civil War appeared on the big screen in the era before and during the centennial anniversary of the conflict. Two of those films include Gone with the Wind (1939), based on Margaret Mitchell's novel published three years earlier, and Shenandoah (1965), starring Jimmy Stewart. Both films portray Southern families caught up in the Civil War and how the war affected immensely affected their lives. It should come as no surprise that two of the leading hands in these films, which shaped people's perceptions of the Civil War for years to come, likely drew inspiration from their grandfathers, both of whom served in the war.

While filmmakers adapted Mitchell's literature into a film, by creating the story she did, Mitchell's fingerprints are all over the screen version of Gone with the Wind. Mitchell grew up hearing and feeling war stories from her grandfather, Sgt. Russell Crawford Mitchell of the 1st Texas Infantry. Russell was born and raised in Georgia but moved to Texas a couple of years prior to the outbreak of hostilities. Mitchell supported secession and raised a company of Texans to fight in the war. His company voted to enter the scene of war in Missouri. Mitchell, however, "believed the big fighting would be" in Virginia and so resigned his command and joined Company I of the 1st Texas.(1)

Tuesday, September 3, 2019

As Circumstances Permitted: Capt. James Duane and his Reconnaissance of Antietam Creek's Crossings on September 16

Antietam Creek provided a question that George B. McClellan needed to answer. In order to fight the Army of Northern Virginia at Sharpsburg, his army had to navigate across that stream. Doing so presented an issue for the Federals, as straddling a stream in the face of the enemy was a less than ideal situation, something the Union commander experienced in the Seven Days' Campaign. Few officers in the Army of the Potomac were better suited to finding reasonable places to cross the Antietam than Capt. James Duane.

Since his graduation from West Point in 1848, Duane had served in the Corps of Engineers, both in the classroom and in the field. At Antietam, he commanded the Army of the Potomac's Regular Engineer Battalion and served on McClellan's staff.(1)

The situation on the northern end of the Federal line did not present as much of an issue as the state of affairs in the sector of the Ninth Corps when it came to crossing the Antietam. There, Confederate forces positioned themselves overlooking the creek and a major bridge crossing (the Lower, or Burnside, Bridge). In fact, some of the Confederate skirmishers held a foothold on the creek's eastern bank, making any Federal reconnaissance surveying the approaches to the bridge or additional crossing points incredibly difficult. Despite those circumstances, McClellan looked to Duane and his engineers to survey the creek on the battlefield's southern end.

|

| Capt. James Chatham Duane (courtesy of the United States Lighthouse Society) |

The situation on the northern end of the Federal line did not present as much of an issue as the state of affairs in the sector of the Ninth Corps when it came to crossing the Antietam. There, Confederate forces positioned themselves overlooking the creek and a major bridge crossing (the Lower, or Burnside, Bridge). In fact, some of the Confederate skirmishers held a foothold on the creek's eastern bank, making any Federal reconnaissance surveying the approaches to the bridge or additional crossing points incredibly difficult. Despite those circumstances, McClellan looked to Duane and his engineers to survey the creek on the battlefield's southern end.

Tuesday, August 13, 2019

Antietam: The End of the Overland Campaign...of 1862

|

| An unknown Confederate soldier lies dead next to the recent grave of Lt. John A. Clark, 7th Michigan Infantry |

Lee did not plan them all in advance at one sitting. He did not plot his move against McClellan on the Chickahominy as the first step toward the Potomac. Nonetheless, Lee's three operations do connect to make one larger campaign. As events evolved, Lee lifted his eyes from one freed frontier to the next. One campaign grew naturally from the other, and when completed they formed an organic whole. What started as a campaign to relieve Richmond became a campaign to win the war.(1)While Lee and the Confederate high command did not envision driving the Army of the Potomac away from Richmond and then immediately moving north into Maryland, bringing that state into the folds of the Confederacy was a goal for the southern government. However, Lee took advantages of the opportunities that were presented to him, which led to a three-month-long stretch from the end of June to September 1862 that witnessed nearly--but not entirely--constant marching and fighting.

Tuesday, July 9, 2019

Antietam Armament: What Firearms Did Each Army Carry in the Maryland Campaign?

|

| This blown-up view of the 93rd New York Infantry taken shortly after the Maryland Campaign shows the infantrymen holding their Enfield rifled muskets (Library of Congress) |

Saturday, June 29, 2019

McClellan's Guns of Position: Part 4

An image is worth one thousand words, so the saying goes. Well, it has taken 3,684 words and numerous pictures and graphics to bring us to Part 4 (and the conclusion, sort of) of the "McClellan's Guns of Position" series. Hopefully, this series has opened readers' eyes to the importance of the guns of position at Antietam. Putting together this series has been revelatory for myself and I am walking away from it with a much greater appreciation of the role they played during the Battle of Antietam.

When originally envisioning this series, I wanted the conclusion of it to not be filled with so many heavy-hitting statistics (that is what parts 1, 2, and 3 are for) but rather with modern pictures from the guns of position locations that drive home the points made in the first three parts. Last winter, I had the pleasure of accompanying many of Antietam Battlefield Guide friends onto the former Ecker Farm to take a gander at what those artillerists saw of the Confederate positions from September 16 to 18, 1862. That trip was the genesis of this series. And while there are many more trees crowning the Ecker Farm Ridge south of the Boonsboro Pike today than there were in 1862, the views were still spectacular.

I will let the pictures speak for themselves.

When originally envisioning this series, I wanted the conclusion of it to not be filled with so many heavy-hitting statistics (that is what parts 1, 2, and 3 are for) but rather with modern pictures from the guns of position locations that drive home the points made in the first three parts. Last winter, I had the pleasure of accompanying many of Antietam Battlefield Guide friends onto the former Ecker Farm to take a gander at what those artillerists saw of the Confederate positions from September 16 to 18, 1862. That trip was the genesis of this series. And while there are many more trees crowning the Ecker Farm Ridge south of the Boonsboro Pike today than there were in 1862, the views were still spectacular.

I will let the pictures speak for themselves.

Wednesday, June 26, 2019

"The Rebels Would Eat Me Up": Attempting to Read Joseph Hooker's Mind on September 16

George B. McClellan's movement of Joseph Hooker's First Corps across Antietam Creek on the afternoon of September 16 is a fascinating move to me, perhaps the most fascinating of the entire Maryland Campaign. Hooker's corps of roughly 9,000 men sent across the creek alone to face the whole Army of Northern Virginia is a gutsy decision.

Hooker himself expressed some displeasure with his situation to McClellan in person. "If re-enforcements [sic] were not forwarded promptly, or if another attack was not made on the enemy's right, the rebels would eat me up," wrote Hooker. Clearly, Hooker was nervous about his and his corps' situation on September 16. Despite that, he attacked the enemy in his front the next morning with the Federal Twelfth Corps backing him up.

Tuesday, May 28, 2019

McClellan's Guns of Position: Part 3

This post is Part 3 in a series. Click the hyperlinks to visit Part 1 and Part 2.

Before posting modern images of the viewpoint of McClellan's guns of position, it would be best to examine those guns' impact on the Battle of Antietam from the Army of the Potomac's perspective. Part 2 discussed the guns' fields of fire and range on the Antietam battlefield before sharing quotes from the Confederate perspective of the damaging fire George B. McClellan's guns of position provided. Let's now discuss the Federals' perspective of that same damaging fire.

Most, but not all, of McClellan's heavy guns constituted the Army of the Potomac's Artillery Reserve under the command of Lt. Col. William Hays. During the Maryland Campaign, that organization consisted of 27 commissioned officers and 716 enlisted men present for duty. Their armament comprised a total of 34 guns in seven batteries.(1)

After deploying the guns of position on the elevation east of Antietam Creek, the gunners went to work picking their targets across the stream. Thanks to their positioning, the gunners were "afforded an ample opportunity to test the efficiency of these heavy field pieces," according to Capt. Elijah Taft.(2) Indeed, the guns of position posted on the Ecker Ridge were presented with an abundance of targets and used their location on the battlefield to their advantage. Francis Palfrey, an Antietam veteran and later author on the battle, wrote of the view from the positions of the artillery on the Ecker Ridge: "Standing among those guns, one could look down upon nearly the whole field of the coming battle, while the view was perhaps more complete from the high ground on the left of the road, where some of the Fifth Corps batteries were placed. From this point one could look to the right through the open space between the 'East and West Woods.'" He continued: "The conformation of the ground was such that these central Federal batteries could sweep almost the whole extent of the hostile front. Some of them had a direct fire through the space between the East and West Woods, and others of them could enfilade the refused left wing of the Confederate army."(3) Experienced artillerist Henry Hunt echoed Palfrey's assessment when he reported of the guns of position that "[t]heir field of fire was extensive, and they were usefully employed all day."(4)

Before posting modern images of the viewpoint of McClellan's guns of position, it would be best to examine those guns' impact on the Battle of Antietam from the Army of the Potomac's perspective. Part 2 discussed the guns' fields of fire and range on the Antietam battlefield before sharing quotes from the Confederate perspective of the damaging fire George B. McClellan's guns of position provided. Let's now discuss the Federals' perspective of that same damaging fire.

Most, but not all, of McClellan's heavy guns constituted the Army of the Potomac's Artillery Reserve under the command of Lt. Col. William Hays. During the Maryland Campaign, that organization consisted of 27 commissioned officers and 716 enlisted men present for duty. Their armament comprised a total of 34 guns in seven batteries.(1)

|

| Lt. Col. William Hays commanded the Army of the Potomac's Artillery Reserve |

Thursday, May 23, 2019

McClellan's Memorial Day Visit to Antietam

This article is reposted from the Emerging Civil War blog.

|

| The Private Soldier Monument was dedicated in 1880 and sits at the center of Antietam National Cemetery |

“Only once a year, the comrades of the Grand Army march in sad procession to place flowers on the graves of those who died, side by side with the living, in defence of their country and their homes. This is the only public exhibition of the veterans of the Grand Army.” So wrote the Boston Herald‘s editor in 1885, twenty years after the Civil War’s conclusion.

Sharpsburg, Maryland’s citizens greeted Memorial Day every year with reverence. Every day, the graves of 4,776 Union soldiers looked down on their quiet town. The stories of what they experienced on Wednesday, September 17, 1862, could never be silenced or forgotten. Memorial Day was, by then, a large American commemoration, something the press covered widely. Veterans across the country gathered in a spirit of remembrance for their dead comrades.

Civilians gathered each Memorial Day inside the stone walls of Antietam National Cemetery to pay their respects. The keynote speaker for the 1885 ceremony drew great attention and brought throngs of people to the burying ground in Sharpsburg.

Tuesday, April 30, 2019

Inspecting the Third Brigade of the Pennsylvania Reserves in the Field of the Maryland Campaign

In an army of units that saw heavy fighting since the beginning of the Seven Days, fewer Federal divisions suffered worse than the Pennsylvania Reserve Division under the command of John Reynolds. Total casualties during the Seven Days' Campaign total approximately 2,600 men. Another 610 names joined the list at Second Bull Run in late August. On the eve of the Maryland Campaign, the division was a shell of itself.(1)

While researching in the National Archives today, I stumbled on this incredible inspection report of the division's 3rd Brigade, commanded by Lt. Col. Robert Anderson at the Battle of Antietam. It gives a good glimpse into the state of the brigade, and the division as a whole, on the eve of the battles of South Mountain and Antietam.

|

| Brig. Gen. John F. Reynolds |

Monday, April 29, 2019

Killing the Kinks: The Unlikely Command Relationship Between George B. McClellan and Joseph Hooker

George B. McClellan is sometimes portrayed as one who promoted his advocates and damned his opponents within his own army. When it comes to McClellan's generalship in command of the Army of the Potomac, there is one major exception to that oft-held view--his appointment of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker to take command of the First Corps during the Maryland Campaign.

Hooker was an outspoken antagonist of McClellan's generalship and felt slighted by McClellan's report of the Battle of Williamsburg that did not give Hooker and his division enough credit. During the Peninsula Campaign, Hooker confided to a friend about McClellan, "He is not only not a soldier, but he does not know what soldiership is."(1) In the aftermath of Second Bull Run, artillerist Charles Wainwright noted in his diary this quote from Hooker: "if they had left McClellan in command this never would have happened." Wainwright, in his own words, followed up Hooker's remarks by saying, "This was a great deal for Hooker to say, as he had no love for McClellan."(2)

Hooker was an outspoken antagonist of McClellan's generalship and felt slighted by McClellan's report of the Battle of Williamsburg that did not give Hooker and his division enough credit. During the Peninsula Campaign, Hooker confided to a friend about McClellan, "He is not only not a soldier, but he does not know what soldiership is."(1) In the aftermath of Second Bull Run, artillerist Charles Wainwright noted in his diary this quote from Hooker: "if they had left McClellan in command this never would have happened." Wainwright, in his own words, followed up Hooker's remarks by saying, "This was a great deal for Hooker to say, as he had no love for McClellan."(2)

|

| Joseph Hooker (left) and George B. McClellan (right) rarely saw eye to eye. |

Wednesday, February 20, 2019

McClellan's Guns of Position: Part 2

In Part 1 of this series, I examined the makeup of the Army of the Potomac's "guns of position" during the Maryland Campaign before focusing on the core of that artillery grouping, the 20-lb. Parrott rifle. For Part 2, I will look at the effectiveness of these guns and their importance to the Federal army at Antietam.

First, it is important to establish the fact that even though these guns remained on the east side of Antietam Creek for the entirety of the battle, they did not sit out the fighting. There is a tendency among people visiting the battlefield to think that Federal soldiers positioned east of the creek (with the exception being those around the Burnside Bridge) were merely spectators to the action on the other side of the creek. This is not true, especially in the case of the "guns of position." Even the Union infantry east of the creek fell victim to enemy artillery shells and did sustain minor casualties.

With their extensive range and excellent fields of fire, McClellan's and Hunt's heavy guns played a large role in the battle and in McClellan's planning during the actions along Antietam Creek. According to the Table of Fire for 20-lb. Parrotts, they had a maximum reach of 4,400 yards or 2.5 miles. This distance could be reached by a shell fired at 15 degrees and would take the shell over 17 seconds from the time it was fired to reach its target.

First, it is important to establish the fact that even though these guns remained on the east side of Antietam Creek for the entirety of the battle, they did not sit out the fighting. There is a tendency among people visiting the battlefield to think that Federal soldiers positioned east of the creek (with the exception being those around the Burnside Bridge) were merely spectators to the action on the other side of the creek. This is not true, especially in the case of the "guns of position." Even the Union infantry east of the creek fell victim to enemy artillery shells and did sustain minor casualties.

With their extensive range and excellent fields of fire, McClellan's and Hunt's heavy guns played a large role in the battle and in McClellan's planning during the actions along Antietam Creek. According to the Table of Fire for 20-lb. Parrotts, they had a maximum reach of 4,400 yards or 2.5 miles. This distance could be reached by a shell fired at 15 degrees and would take the shell over 17 seconds from the time it was fired to reach its target.

Tuesday, February 12, 2019

McClellan's Guns of Position: Part 1

When George McClellan reached the eastern banks of the Antietam Creek on the afternoon of September 15, 1862, one of his first orders was issued in person to his Chief of Artillery, Brig. Gen. Henry Hunt. He told Hunt near sundown "to select places for our guns of position."(1) These guns had a large role to play in the upcoming fight and in McClellan's battle plan.

A few months ago, I had the pleasure of being able to walk the ground where many of these guns were positioned on September 17 on a ridge owned at the time of the battle by the Ecker family. The wartime Ecker house still stands. This prominent ridge, what I will refer to as the Ecker Ridge, stands prominently along Antietam Creek's east bank and has a commanding view of much of the Antietam battlefield. It is easy to see why it was prized by McClellan and Hunt and why the guns posted there were so effective.

Since it was such a rare treat to visit, I took plenty of pictures, trying to capture the Federal artillerists' views as best as I could. But before posting those, in what will be Part 4 of this series, I first wanted to take a closer look at these guns of position.

A few months ago, I had the pleasure of being able to walk the ground where many of these guns were positioned on September 17 on a ridge owned at the time of the battle by the Ecker family. The wartime Ecker house still stands. This prominent ridge, what I will refer to as the Ecker Ridge, stands prominently along Antietam Creek's east bank and has a commanding view of much of the Antietam battlefield. It is easy to see why it was prized by McClellan and Hunt and why the guns posted there were so effective.

Since it was such a rare treat to visit, I took plenty of pictures, trying to capture the Federal artillerists' views as best as I could. But before posting those, in what will be Part 4 of this series, I first wanted to take a closer look at these guns of position.

|

| Most of the guns of position can be seen overlooking Antietam Creek on the Ecker Farm Ridge in this map of the Antietam Battlefield Board. |

Saturday, February 2, 2019

Close and Concentrated: 9th Corps Artillery Conquers the Burnside Bridge

I had always thought of the fight for the Burnside Bridge as one of infantry. The 2nd and 20th Georgia stoutly defending the bridge and the charge of the 51st New York and 51st Pennsylvania dominate our interpretation of the action there. It was not until today while hiking the Burnside Bridge sector of the Antietam battlefield with my good friend and artillery guru Jim Rosebrock (check out his excellent blog here) that I realized how crucial of a role Ambrose Burnside's and Jacob Cox's artillery played in cracking the conundrum of how to get their men across Antietam Creek.

The 9th Corps had 53 guns at Antietam, according to Curt Johnson's and Richard C. Anderson, Jr.'s book Artillery Hell. At various points of the fight for the Burnside Bridge, anywhere from 21 to 29 of those guns fired directly on the Confederate infantry defending the bridge or the nearby Confederate artillery that supported the infantry.

As attack after attack against the bridge and its Confederate defenders failed, there is a marked effort on the part of Burnside, Cox, and 9th Corps artillery chief George Getty to use artillery to drive the enemy away from the banks of Antietam Creek. While the 9th Corps' position always allowed it to converge the fire of its artillery onto the Confederate defenders, as the day wore on, 9th Corps batteries began shrinking their ring of fire, ensnaring the Confederates and ultimately helping drive them away.

The 9th Corps had 53 guns at Antietam, according to Curt Johnson's and Richard C. Anderson, Jr.'s book Artillery Hell. At various points of the fight for the Burnside Bridge, anywhere from 21 to 29 of those guns fired directly on the Confederate infantry defending the bridge or the nearby Confederate artillery that supported the infantry.

As attack after attack against the bridge and its Confederate defenders failed, there is a marked effort on the part of Burnside, Cox, and 9th Corps artillery chief George Getty to use artillery to drive the enemy away from the banks of Antietam Creek. While the 9th Corps' position always allowed it to converge the fire of its artillery onto the Confederate defenders, as the day wore on, 9th Corps batteries began shrinking their ring of fire, ensnaring the Confederates and ultimately helping drive them away.

Tuesday, January 22, 2019

A Game of Numbers: Robert E. Lee's Assumptions about the Federal Garrisons in the Shenandoah Valley

Standing and fighting at Sharpsburg. Pickett's Charge. Each of these decisions could rightfully be labeled as Robert E. Lee's greatest mistake during his Civil War career. But one that often flies under the radar is the decision Lee made earlier in the Maryland Campaign to divide his army and send a large portion of it into the Shenandoah Valley to subdue the Federal garrisons positioned in Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry. A bold plan to be sure, this plan alone was not the undoing of Lee's campaign. Instead, it was the assumptions he made about how quickly his soldiers could open the Confederate supply line in the Shenandoah Valley.

Robert E. Lee was aware of the Union garrisons in the Valley before his men set foot on Maryland soil. But his crossings near Leesburg armed him with the belief that his intervention between those garrisons and Washington City and Baltimore would force the evacuations of Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry. It did not. Before Lee could advance his army farther north into Pennsylvania, he had to deal with the enemy in his rear to open the Valley as a supply route and, if needed, route of retreat back to Virginia.

On the evening of September 9, 1862, staff officers and couriers emanated from Lee's headquarters outside of Frederick. The riders delivered multiple copies of Special Orders No. 191 to Lee's subordinates. The orders outlined the division of the Army of Northern Virginia into multiple pieces, three of which, led by Stonewall Jackson, Lafayette McLaws, and John Walker, would take different routes to intercept, destroy, or capture the enemy garrisons at Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry. When the orders went into effect the next day, Lee anticipated that these three wings would wrap up the operations in the Valley quickly--perhaps as early as September 12--before the army reunited and continued on its trek north.

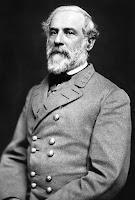

|

| Robert E. Lee |

On the evening of September 9, 1862, staff officers and couriers emanated from Lee's headquarters outside of Frederick. The riders delivered multiple copies of Special Orders No. 191 to Lee's subordinates. The orders outlined the division of the Army of Northern Virginia into multiple pieces, three of which, led by Stonewall Jackson, Lafayette McLaws, and John Walker, would take different routes to intercept, destroy, or capture the enemy garrisons at Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry. When the orders went into effect the next day, Lee anticipated that these three wings would wrap up the operations in the Valley quickly--perhaps as early as September 12--before the army reunited and continued on its trek north.

Sunday, January 13, 2019

John Pope's Take on Joseph Mansfield

John Pope's personality is often viewed negatively by historians. Quotes from Pope haters can be easily found and are often repeated in Civil War historiography. Sometimes, it reaches the point where one wonders if anyone could have gotten along with him or vice versa.

Pope's Military Memoirs, edited by Peter Cozzens and Robert I. Girardi, offer an eye-opening look into this divisive general. One quote in particular though caught my attention. It was Pope's description of Joseph Mansfield and his personality, looks, and bravery. Quotes like this are revealing, especially when Pope ties Mansfield's personality traits to his fate at Antietam. The two served together in Mexico, Mansfield as Pope's superior officer. "Pope took to Mansfield at once," wrote Pope's biographer Peter Cozzens. It appears Pope's favorable view of Mansfield remained until his dying day.

General Mansfield was of middle height and robust figure. He had a broad and rather ruddy face, with a thick shock of white hair and beard. He was a man of kindly disposition and very just; but, as I have said before, he was rather fussy and fond of meddling with his subordinates, so that, although all of his officers exulted in his behavior in battle and were immensely proud of him for some time after the battle was over, he soon reduced them to their old feeling that he tormented and persecuted them unwarrantably. He was still a comparatively young man when he was killed at Antietam, but I think it may be said of him that his complete recklessness and his apparently irresistible inclination to seek the most exposed and most dangerous places on a field of battle, of necessity deprived him of the power to use his great military abilities and acquirements to the best advantage for the army or the government. He was a gallant soldier and a true and loyal man and will always be remembered with pride and respect by those who knew him in those old days.

Pope's Military Memoirs, edited by Peter Cozzens and Robert I. Girardi, offer an eye-opening look into this divisive general. One quote in particular though caught my attention. It was Pope's description of Joseph Mansfield and his personality, looks, and bravery. Quotes like this are revealing, especially when Pope ties Mansfield's personality traits to his fate at Antietam. The two served together in Mexico, Mansfield as Pope's superior officer. "Pope took to Mansfield at once," wrote Pope's biographer Peter Cozzens. It appears Pope's favorable view of Mansfield remained until his dying day.

|

| Joseph K. F. Mansfield |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)